Afro-centric Library and Information Science discourse analysis

Background

This paper is a discourse analysis intended to contribute to an understanding of Library and Information Science (LIS) in the African context with a small twist on the past, given its heavier accent on publications in the past century. It postulates a few questions related to LIS in Africa and addresses these questions through an analysis of publications from Africa or about Africa. Discourse in the context of this paper is considered to be the formal treatment of a subject (i.e. LIS) in scholarly publications in an attempt to conceptualise LIS through the lens of African scholars.

Conceptualising information, its dynamics and pragmatic use at individual, organisational and societal levels in the midst of its rapid growth is of paramount importance to the information profession. Internationally, information professionals collaborate in various ways and settings to enhance their capacity to deal effectively with the complexities and dynamics of information. The Conference on conceptions of Library and Information Sciences (CoLIS) is one example of such a collaboration. CoLIS started in 1991 and aims to provide a broad arena for critically exploring and analysing research in information-centred disciplines such as Computer science, Information Science and Library Science, as they are fundamental to the pragmatic use of information either from the system or the human orientation 1. CoLIS tends to provide a platform for the analysis of various themes as they relate to the theoretical, empirical and technical development of information-centred disciplines, particularly LIS 2.

Africa is one of the most deprived continents of the world and needs essential information to alleviate its situation. Ironically, in practice the reverse is the case, because information might be one of the most neglected resources in Africa 3. Information may be among lower level issues in the hierarchy of African priorities, yet African countries are facing political, economic, social and technological development upheavals in varying degrees. In the midst of deprivations and turmoil, information and its effective delivery cannot be overemphasised. Since effective information service delivery is one of the primary concerns of LIS, for a few decades library and information professionals in Africa have been preoccupied with the process of re-evaluating the new roles of libraries and information centres in addressing the challenges on the African continent in an endeavour not only to influence social change and regional development through information sharing, but also to improve libraries and information centres in Africa and understanding of the complexities of information 4. Of importance is the recognition by African information professionals of challenges evident on the continent, hence their initiatives to engage in research to reflect constantly on the situation on ground level, delineate trends and formulate possible solutions related to information and to meet through forums such as the Standing Conference of Eastern, Central and Southern Africa Library and Information Associations. Clearly African LIS scholars collaborate in various ways, such as in scholarly publications 5.

The crescendos of information and the ever-changing information provision landscape affect people at various levels 6, but the impact on information professionals is greater, as they are concerned with information service delivery to contribute positively to the knowledge economy. As a result, the role of the information profession and its affiliated discipline, LIS, is constantly in the spotlight and certainly poses challenges in keeping informed about the latest trends and developments in the information sector. One of the challenges facing the information profession in Africa is that professionals are operating within a heterogeneous society ranging from a majority of extremely poor and illiterate people to well-educated and affluent people, who are in the minority. Other challenges include inadequate information and communication infrastructure, the HIV and AIDS pandemic, malaria and tuberculosis, food shortages and extreme poverty and gaps in governance in terms of appropriate regulatory frameworks 7. A reflection on the African situation and its information profession, particularly LIS in the African context, underpins this paper.

The purpose of the paper

The purpose of this paper is to delineate the term LIS through an Afro-centric approach by tracing the LIS discourse through research and scholarly publications. Afro-centric in this paper denotes the specific focus on LIS publications on Africa by Africans and literature by foreigners about Africa denoting the Africana context as explained by Igbeka and Ola 8. Notably, some countries in Africa are extremely poor and lack LIS schools and others, such as South Africa, have better economies and well-established LIS schools, as well as higher research output 9. Consequently, there is a disparity in the distribution of LIS schools in Africa, clearly delineated by Ocholla 10 ; hence the LIS research output emanates from a few countries in Africa. Although the LIS discourse followed in this paper is Afro-centric, significant contributions come mainly from a few African countries such as South Africa, Nigeria and Kenya, which are leading in LIS education and research. Nonetheless, a plethora of LIS publications on Africa exists in the form of journals, conference papers and proceedings that made this discourse analysis feasible 11. A significant number of African LIS publications are related to LIS education, in particular the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) in LIS education 12, LIS education and training including curriculum 13 and LIS research trends in Africa 14.

This paper is a comprehensive analysis of LIS publications from and about Africa between 1990 and 2012 to address the questions below and hence the paper is structured accordingly :

– What is the definition of the term Library and Information Science ?

– When did the term “Library and Information Science” come into being in Africa ?

– Which terms constitute or are related to Library and Information Science ?

– What are Library and Information Science trends and standards in Africa ?

– What constitutes Library and Information Science education and training in Africa ?

– Which professions form part of the Library and Information Science sector in Africa ?

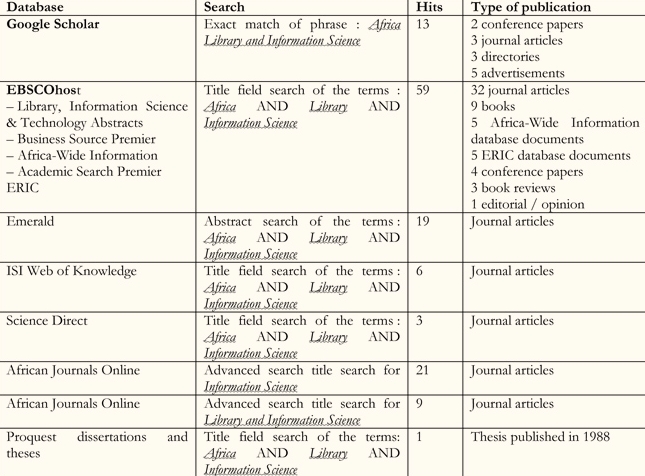

The publications were found through a systematic literature search using the terms « Africa Library and Information Science » in the title field in various databases, as shown in the table below. The abstract field was used when the title field search yielded zero results. Although the table depicts many hits, most of these hits yielded similar records. The choice of database to search was based on familiarity to the author. Additional publications were solicited by perusing the reference lists of the publications found. This was followed by analysis directed by the questions outlined earlier under the purpose of the paper.

What is the definition of the term Library and Information Science?

Although this paper intends to be Afro-centric, definitions of LIS by Africans on Africa were not found, hence this question is addressed from other sources that were not related to Africa per se, even though they involve African scholars citing other scholars to define LIS. However, Rugambwa states that Information Science centres on the study of the conceptualisation of information, and combines an understanding of information technology with the scientific study of human behaviour in its information seeking and processing mode, so as to make full and effective use of the enormous potential power of the computer to store, organise, and manipulate data 15. Furthermore Rugambwa cites Beckman who states that :

Information Science is the science that investigates the properties and behaviour of information, the forces governing the flow of information, and the means of processing information for optimum accessibility and usability. The processes include the origination, dissemination, collection, organisation, storage, retrieval, interpretation, and use of information » 16.

There are more definitions of LIS, such as :

an interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary field that applies the practices, perspectives and tools of management, information technology, education and other areas to libraries such as the collection, organisation, preservation and dissemination of information resources and the political economy of information » 17.

LIS is essentially concerned with providing instruments (documents, organisation, bibliographies, indexes) to enable people to become better informed through the use of documents 18.

In the process of defining LIS, other African scholars seemed to be concerned about the direction and future of library and information education, for example Ocholla and Bothma 19, Fayose 20, Gupta and Gupta 21 and Dick 22. While they are engaged in mapping directions for LIS education, they pointed out certain views such as the perception of LIS as an applied discipline oriented more narrowly to professional practice, on the one hand, and as a foundational discipline for the purpose of a broader basic education on the other 23. It is evident from Dick that the LIS discipline has been questioned at some point, such that some deem it an interdisciplinary field borrowing from other, more established, social sciences while others maintain that it is a discipline in its own right 24. Another stance is that Information Science is a discipline that really produces more « soft » than « hard » knowledge, and more applied than pure knowledge 25. This contention is debatable, as one may ask what hard and soft knowledge are and also what applied and pure knowledge are. Whether LIS is considered interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary or a discipline, it is evident that African scholars are regularly reflecting (through research) on LIS education and training on the continent 26. Aina and Mooko mention that research is crucial for information professionals in Africa, since the profession itself was imported wholesale from Western Europe in the early part of the last century 27.

On the one hand Rugambwa acknowledges that Information Science emerged as a discipline in response to the explosive growth of the world’s scientific and technical literature in the period after 1945 (World War II) as a result of the growing economic and social importance of information technology and the expanding role of information as a central element in contemporary life 28. On the other hand, Aina and Mooko indicate LIS as an interdisciplinary and fast-growing profession in the world with an important bearing on research in other fields 29.

When did the term « Library and Information Science » come into being in Africa?

The term LIS in Africa is aligned in this document with the beginning of LIS-related education in Africa. Some of the Afro-centric publications that were studied point out that apart from South African LIS schools, LIS started as early as 1938 in Africa30. Aina indicates that formal training programmes for information workers started in English-speaking Africa in 1959, when the first Librarianship course was started at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria 31. Prior to this, most trainees were prepared for the British Library Association’s examinations through informal training programmes mounted by practising librarians, and the courses offered at Ibadan prepared trainees for these examinations 32. On the contrary, Ocholla mentions that South Africa has a longer history of LIS education than other African countries, dating back to 1938 33. From Ocholla and Bothma one gathers that LIS education began after 1960 in Africa 34. These scholars add that although current LIS education in Africa does not exclusively target the training and education of librarians, originally LIS schools’ major focus in the education and training area was Librarianship. In principle they are drawing a distinction between Librarianship and LIS education. Another distinction of Information Science timing in Africa is found in Rugambwa who states that the term Information Science became widely used after 1958 even though its definition remained contentious 35.

Which terms constitute or are related to Library and Information Science?

African publications in the early 1980s and 1990s seemed to have used the terms LIS, Information Studies, Library Science, Library studies, Librarianship and Information Science interchangeably, as noted from publications such as those by Gupta and Gupta and Rugambwa 36. Over time, demarcations were clarified, particularly between Library Science and Information Science 37. Nonetheless, Rugambwa maintains that LIS is related to various terms such as Information Science, information systems, Computer science, informatics, etc. The variations between terms are affiliated with university programmes, which in the past were identified by their primary purpose, the background of students and the career paths pursued by graduates of these programmes 38.

What are Library and Information Science trends and standards in Africa?

The eradication of qualifications in Librarianship alone as a result of limited job opportunities in libraries owing to the minimal or total lack of expansion of libraries in Africa brought about new trends in LIS in Africa 39. The need to distinguish between Library Science and Information Science also had an impact on the LIS trends in Africa 40. Countries, including South Africa and Namibia, have explored the issue of clarifying the distinction between Library Science and Information Science. The differences of emphasis in the curricula offered are typical of many other countries. The effect of this difference in emphasis is a change in nomenclature by some institutions for their departments and degrees to emphasise « information » instead, or to the exclusion, of « library » 41.

An evident trend is that of embracing the dynamics of information and the ever-changing information landscape through transformation of departments, curriculum reforms that incorporate ICT, as well as the diversification of the LIS profession. This is marked by LIS education and training becoming highly dependent on modern computer hardware and software, efficient internet access and connectivity, computer literate and highly skilled information technology staff and well-equipped computer laboratories 42.

Curriculum reforms incorporating ICT in LIS education also brought about research on mapping and auditing ICT in LIS education in Africa 43. The number of students enrolling for LIS with diversified qualification programmes offering either broader information orientation or specialised information qualification programmes (such as records management, publishing, multimedia, knowledge management and information technology) has either increased or stabilised 44.

The transformation and changing of names of LIS departments in Africa is an indication of the dynamics of information being accommodated. Underwood and Nassimbeni, as well as Ocholla and Bothma, clearly note that in the past, most departments were simply called Departments of Library Science / Library studies or Librarianship, but over time most departments changed their names to Department of Library and Information Science / studies and later on some departments changed their names to Information Science / studies, while others combined with other (information-related) disciplines such as knowledge management and communication 45.

Another trend is that of African scholars working together to incorporate emerging issues pertinent to the information profession, such as information ethics. An African network for information ethics exists, which is concerned with information ethics in LIS 46. The network is growing and spearheads the inclusion of information ethics in the LIS education curriculum ; it has organised several conferences and workshops focusing on pertinent information ethics issues. Deliverables are already seen in the form of scholarly publications such as Africa reader on information ethics 47.

What constitutes Library and Information Science education and training in Africa?

According to Rugambwa, the common core competencies identified in Information Science education can be broadly classified to include : (1) information resources and services (sources and users) ; (2) research (quantitative) methods ; (3) information systems analysis, design and evaluation ; (4) information systems and services in individual sectors (e.g. health, agriculture, etc.) ; (5) information technology modules ; (6) information retrieval systems; and (7) management of information systems and services 48.

According to Ocholla and Bothma, LIS education in Africa focuses on management, information seeking and retrieval, knowledge organisation, knowledge representation and user studies, with increased use of technology. Moreover, the curricula also increasingly provide core courses or electives / auxiliaries in knowledge management, multimedia, publishing, records management and ITC. Furthermore, training is offered through various modes such as contact (full-time or part-time) and distance learning that is predominant at the University of South Africa 49.

Snyman adds that LIS professionals need to have a sound theoretical background, good interpersonal and teamwork skills, the ability to think analytically and critically and ICT competencies 50. The requirements outlined by Snyman suggest the challenges for LIS educators in balancing the human-centred, theoretically rich modules with critical and analytical goals that are ICT-directed 51.

Ocholla has confirmed findings in his earlier studies emphasising sound education in management, ICTs, information searching, analysis and synthesis, as well as the ability to do practical work 52. He defends the teaching of cataloguing and classification on the basis that they provide knowledge about the analysis and synthesis of information, as well as knowledge of the nature and structure of a given collection. Aina, bearing in mind the illiterate population of rural Africa, recommends that the LIS schools evolve curricula that are mission-oriented and geared towards meeting African needs and the information demands of farmers, artisans, grassroots politicians, government policy makers and decision makers, etc. 53

Which professions form part of the Library and Information Science sector in Africa?

Snyman reports on a study in which she analysed the job advertisements in the three national newspapers with the highest circulation, from January to August in 1999. She found that of the 250 jobs involving a significant amount of information handling, 114 positions were potentially open to trained information workers 54. These positions included library workers, information workers, information systems specialists, information and knowledge managers, information analysts and research workers, advisors and consultants, records managers, archivists, teachers and trainers and managers of a library association 55.

According to Reagon (2005), as technology advances the LIS profession with its sophisticated ICTs to perform information management and dissemination, and in view of information workers’ unique set of information skills, new opportunities will be available for these workers to become specialist consultants on information management and retrieval 56. Traditional workers should be able to move out of the « institutionalised » library setting to the « deinstitutionalised » information environment where they can perform a variety of tasks. New job opportunities for librarians include « information broker », « website developer », « information specialist », « knowledge manager », « software librarian » and « information analyst » 57.

Conclusion

This paper discussed the term LIS in the context of Africa, concentrating on the past, given the dates of most of the sources selected. It defined LIS as a discipline, including the debates as to whether it is interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary or perhaps, not even a discipline. The trends pertaining to LIS due to the dynamics of the information landscape were discussed, with a special focus on Africa. The paper also highlighted LIS education and training in Africa, as well as professions related to this field and clearly indicated that it has been transforming and has not remained static, to accommodate the ever-changing information landscape. There is evidence that LIS scholars are concerned about their field, given the diverse literature sources written by both African scholars and scholars from other continents with special interest in Africa. One also realises that LIS scholars are keeping abreast with the latest development in ICT and have incorporated these in their education and training programmes. Although it was outside the scope of this paper to analyse LIS literature on rural communities in Africa, considering that majority of Africans live in destitute rural conditions, more work still needs to be done to improve the situation of rural people in Africa who are mostly poor and illiterate, as described by Kaniki 58. As part of defining the Afro-centric LIS, future analysis should consider focusing more on rural African communities.